SIMLab's experience in Kenya: Implementing a mobile money management tool and training approach in the last mile

36

minute read

This case study describes the midterm progress and learning from a two-year project, funded by the UK Government’s Department for International Development (DFID). The project introduced a new mobile money management software to forty ‘last-mile’ organizations, all of which faced significant infrastructure, access and capacity constraints making the transition to cashless processes cumbersome and unpredictable. This case study seeks to shed light on the challenges of extending mobile money to the last mile, through a human and organization-centric lens. Although the project operated only in Kenya, but with the learning is applicable globally.

Social Impact Lab (SIMLab) helps people and organizations to use inclusive technologies to build systems and services that are accessible, responsive, and resilient. Until December 2014, SIMLab was the home of the FrontlineSMS project, a suite of software that helps organizations build services with text messages. FrontlineSMS has now spun out as a separate, for-profit social enterprise, and SIMLab continues to focus on solving many of the challenges of implementing projects using inclusive technologies. They support implementation, the sharing of learning and synthesis of best practice, and advocate to decision-makers and donors for policy-level change.

SIMLab defines inclusive technologies as those which embody values critical to truly scalable, locally-owned impact; accessibility, ease of use, interoperability, and sustainability. Mobile is a key example—SMS and voice telephony reach all of the world’s 3.6 billion mobile subscribers—as is radio, a critical technology for broad reach at relatively low cost. We also embrace both ends of the spectrum of inclusive tech—the increasing availability and affordability of cheap web-enabled phones and mobile data make them more accessible for relatively disconnected communities, and more analogue communications technologies, such as public criers, noticeboards and human networks, like religious structures and community leadership, reach into even the most remote and disconnected communities.

SIMLab’s Last Mile Mobile Money Project helps small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and under-resourced organizations explore available tools to realize the latent potential in mobile value transfer technologies for social change. SIMLab helped partners to break down barriers to innovation; both internally, through change management and business process consulting, and externally, through trainings on how to engage with and educate end-users to begin using accessible mobile money technologies. Through this project, SIMLab has been able to help organizations realize the uses and limitations of inclusive technologies and mobile money, while better understanding the types of organizational characteristics necessary in the implementation of digitization and cashless systems.

The 2014 annual report of the Africa Progress Panel (APP), a group headed by Kofi Annan, highlighted economic development as one of three major areas where progress was needed. For wealthier communities, financial inclusion is fairly easy—transferring, saving, and managing money are just an ATM or app away. For last-mile and low-income communities, these processes are not only far away, they’re often impossibly complex and exclusionary. Poor physical infrastructure (roads, electricity), security risks, and lack of financial capital all prohibit those in last-mile communities from accessing global and regional markets, value chains, and financial services. These barriers preclude rural, poor, and other marginalized populations from accessing resources that could facilitate economic development—from starting their own businesses, accessing markets, insuring their crops, and planning for their future.

These populations, often referred to as ‘unbanked’ for their lack of access to formal bank accounts, and the small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and NGOs that serve them are impacted in very practical ways. For example, to access services or transmit funds, people may have to travel long distances while carrying large sums of cash, incurring heavy transportation costs and leaving them vulnerable to personal security risks.

While approximately 2.5 billion people in developing countries worldwide are classified as ‘unbanked,’ more than 1 billion of them have access to a mobile phone, through which people in over 89 countries (60% of the developing world)1 can now access mobile money services.

In 2007, Kenya’s leading mobile network operator, Safaricom, created the world’s most successful mobile money platform to date, Kenya’s M-PESA. M-PESA currently has over 19 million users, and is globally lauded as a disruptive and pioneering innovation, which has changed the financial landscape, not only in Kenya, but all over the world, as similar services spring up elsewhere. In Tanzania, Uganda, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Afghanistan, the Philippines and South Africa, mobile money uptake is increasing, although no other market yet matches Kenya for mobile money adoption.2 Bill payment services by large businesses are increasingly common, and M-PESA users last year sent 11 billion Kenya Shillings per month through the service.3 For peer-to-peer (P2P) transactions such as urban to rural remittances, M-PESA has been transformative.

The challenges

For the majority of businesses in Kenya, however, M-PESA seems still to be out of reach, although during the period of SIMLab’s project, Safaricom has launched numerous products trying to gain traction in this market. PayBill, Lipa Na M-PESA, Lipa Na Karo and M-Shwari each target different transaction types: savings accounts and payments made to businesses that are connected with a bank account, over the counter transactions, school fees, and short term micro-mobile loans respectively. These platforms are typically relatively expensive for the company to get set up on and use, require a reliable internet connection to use successfully and can take months to acquire. Some require training, and none are designed with the last-mile user in mind.

SIMLab, with support from The UK Department for International Development (DFID)’s Global Poverty Action Fund (GPAF), set out to explore whether providing a new type of platform to organizations like this could help them to implement mobile money, and in so doing, could improve economic livelihoods in rural Kenya. Our theory of change, essentially, was that mobile money could be a transformative tool for rural schools, NGOs, SMEs and Savings and Cooperative Credit Organizations (SACCOs), but that the lack of affordable offline management platforms was having a chilling effect. With a better platform and hands-on support to get started, organizations would be able to begin using mobile money and their end-users—parents and children, beneficiaries, customers and borrowers—would gain all the benefits of mobile money.

Even in Kenya, the mobile value transfer market is still new, and as such the market and ecosystem is still spreading and is often inefficient and uneven in coverage. In the most rural populations, many people do not use M-PESA, or only use it to receive remittances from other parts of Kenya, and immediately exchange their balance for cash. Part of the reason for this is low availability of mobile payments for goods in these areas. An important goal of the project was to test the value of mobile money in a variety of sectors and types of organizations, both to learn, and as an advocacy tool.

In a two-year project beginning in January of 2014, the project has supported 40 rural organizations to implement two pieces of software designed and built by FrontlineSMS in Nairobi, Kenya as part of the FrontlineSMS suite of tools. This case study examines the progress and challenges experienced in the first year and a half of the project.

The software prototypes: PaymentView and Payments

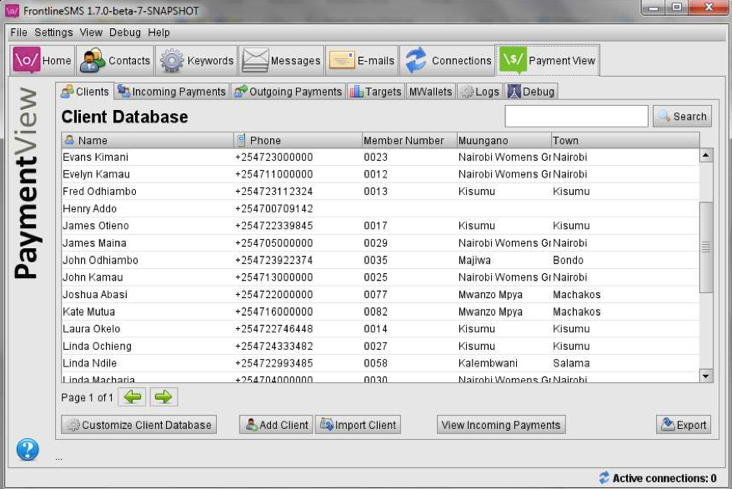

The project began with an existing prototype. PaymentView, built in 2011-2012 with funding from an award won in the Vodafone Americas Wireless Challenge, and intended to fill the gap between Safaricom’s M-PESA mobile money system, and the SMEs who could benefit from using mobile money at an enterprise level. At the idea’s inception, M-PESA offered only the customer-facing USSD and SIM toolkit tools, and an online corporate interface, which was expensive to get set up for and difficult to use, and had relatively limited functionality. Early interviewees in financial services organizations and SMEs confirmed that they were using simple phones to manage transactions, often losing data and unable to easily do basic accounting.

Screenshot of PaymentView interface

PaymentView was based on version 1 of FrontlineSMS, which was released in 2008 and superseded in 2012 by version 2. When building any new tool, it’s important to have your intended user in mind and to know their capabilities and needs, as well as the infrastructure and context in which they’re operating. This user persona can guide software design and development. 10 partners began testing PaymentView in the first year of the project, and the insights we gained were incorporated into the design and features of a new platform, Payments. The key user persona created for Payments was an administrator of one of our target organizations, using a low-end laptop or desktop computer, who does not have stable access to internet.

The decision to begin the project with the older piece of software benefited the design of the eventual product, Payments—but at the cost of some frustration and eagerness to experiment for some of our pilot partners. Although functional, Paymentview proved unreliable, and as it was outdated, was not supported by the FrontlineSMS team. Bugs in PaymentView had resulted in a loss of financial data, delays in processing of transactions, and inability to determine whether payments had been sent, failed or were still being processed. As others have found, innovations must work fully and efficiently in order to maintain a consistent level of engagement with partner organizations.4 If there are any difficulties in the process, implementers quickly lose focus and refuse to use the less reliable parts of the software, as has been the experience with PaymentView. The state of the software caused some frustration in some of the partner organizations who were either trying to use non-functioning elements of the software or who exceeded its in- or outgoing payment limits.

Key Takeaways

-

Certain types of organizations can test prototype software in current development for up to six months, so long as it significantly improves a business process. That time is helpful to allow organizations to change their working practices and end-user communication, and provides an opportunity for technology partners to gather feedback about usability and features. However, continuing beyond six months, risks partner fatigue with the challenges of using an unfinished product. Some partners had high expectations of both PaymentView and Payments, and reverted to their previous systems when the software failed to meet them. In some cases, this was an organization-wide decision, but more commonly, it was a decision made by the person interacting with the software on a daily basis.

-

Hardware requirements must be communicated prior to trainings to ensure all internal approvals are taken care of. When working with rural project staff it is very easy for them to be quickly discouraged by any processes requiring steps outside of their day-to-day obligations. If SIMLab staff left the training without having completed all set-up steps, such as acquisition of a business SIM card and modem, then it was observed that the project was far less likely to go forward.

-

The software can require a steep learning curve, especially for a user with low computer literacy. Due to the time it takes to ‘master’ the software, some users may lose motivation and simply quit. It is not clear how to resolve this challenge, but the high-touch demands of our project suggest that highly scalable approaches to rolling out mobile money in rural, low-infrastructure, low-resource organizations may need to factor in resource-intensive hands-on support, or very high usability.

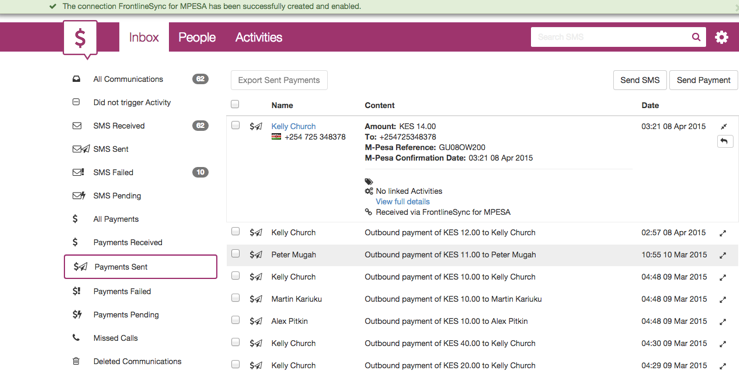

In early 2015, Payments replaced PaymentView and joined a robust and frequently-updated Frontline product set. The software, currently in private beta, has the same core features of PaymentView but benefits from the greater usability, capacity and backend logic of FrontlineSMS v2.

Screenshot of Payments Interface

Payments builds on the FrontlineSMS software’s improved browser-based navigation and adds dynamic financial management automation, allowing organizations to track and manage an entire lifecycle of payments. The logic built into the software allows users to clearly visualize payment histories at both a contact and aggregate level, making it an effective tool for payment reconciliation and monitoring. Payments gives organizations an in-depth look into a client’s entire mobile financial history and also aggregates groups of clients by status of loans (active, default or completed). Additionally, Payments allows organizations to easily and safely send out payments to large groups of beneficiaries—which can drastically cut down on administration time and costs. Payments supports all Safaricom products, including M-PESA’s PayBill and Lipa na M-PESA accounts.

Ultimately, some partners wholeheartedly embraced all other elements of the project, but for various reasons did not elect to roll out Payments or PaymentView. At time of writing, partners are being assessed for the appropriate level and focus of support in the final six months of the project. Our follow-up case study in 2016 will include more detail on the evolution of this aspect of our support.

The hardware

One of the major improvements implemented with Payments was the move away from modems to Android phones as the hardware ‘gateway’.

One of our major problems throughout the project has been in finding and making available hardware work for our purposes. Producing a generic platform for global, multi-sector use that leverages commonly-available technology necessarily has to solve problems of widely varying hardware, unpredictable sourcing, and fragmented smartphone operating systems.

At the time PaymentView was built, modems were a relatively easy hardware to obtain and work with and were the most familiar hardware to the FrontlineSMS development team. However, since the development of the platform, the market of tools available has diversified and modems—ubiquitous in 2012 as the best way to get your laptop online without wifi—are being eclipsed by smartphones. Simple Huawei e-Series modems are still available in most urban shopping districts, but the more sophisticated and expensive Sierra Wireless modems, always hard to source, are now almost impossible to buy wholesale. Modems are also a less attractive purchase for partners, as the modem can only be used to run the software, rendering them single-use items. To overcome this, Payments was designed to connect using a locally-available Android phone, which allows organizations to send and receive payments as well as missed calls, and can double as an office mobile phone, proving helpful for small, low-budget organizations.

Payments, and the Frontline product set more broadly, are useful to partners because they surpass and circumvent the B-to-C offerings of mobile networks and allow users to bypass relationships with operators altogether, by allowing them to run business processes on readily available private accounts.

There is a challenge inherent in working this way, however. These approaches require the user to utilize consumer hardware in ways unintended by the manufacturer, in markets where available phones can vary wildly. In Kenya, for example, a flood of unpredictable Chinese smartphones jostle with second-hand and new Android and iOS smartphones, modems and feature- and ‘dumb phones’.

Operating at the intersection of hardware, software and unpredictable externalities like mobile connectivity and viruses, the prototypes we were testing could sometimes fail, with many potential points of failure:

-

Hardware: Android phones (used to accept payments and send and receive SMS—only Samsung phones successfully sent out payments); Safaricom modems; USB cables and ports; computers and laptops of various makes, models and operating systems; Safaricom SIM cards of various types (personal without M-PESA, personal with M-PESA, Pay Bill, Lipa na M-PESA); and wifi routers.

-

Software: computer operating systems; firewall and anti-virus software; software installers; device installers and drivers; and different versions of FrontlineSMS and Payments

The sheer number of things that can go wrong, interact differently than expected, or simply not work makes troubleshooting and getting organizations set up remotely a very daunting task.

For larger-scale projects to work effectively and avoid these problems altogether, there is no alternative but to work through the solutions offered by the business-facing market—and deal with their inherent limitations of process, cost and functionality. Given the limited nature of even the recently-released M-PESA API, it is clear that the market has yet to produce a truly scalable and effective solution for SMEs in Kenya.

Support

SIMLab offers phone, Skype, email and on the ground support to the organizations with which we work. Partner organizations can run into difficulties with mobile network operators, office computers, mobile money agents and with the software and hardware we provide; so SIMLab resolve the problem either through our own solution or through connecting the organization with someone who can. Depending on the type of support requested, we work with the organization to determine a plan of action and ensure that our suggested solutions truly solve the problem. The FrontlineSMS developer team allocates a few hours a month to fixing bugs on the Payments software, which they will support until the end of the grant period. Occasionally partner organizations may come across a bug in the software, and when this happens, the partner either emails the bug details to SIMLab to pass on to FrontlineSMS, or the bug is described over the phone in detail and transcribed into a support ticket for the FrontlineSMS team to handle. Part of the training with partner organizations covers support and technical troubleshooting, where SIMLab shows partner organizations how to take screen shots, and download Payments system logs, both of which are critical to ensuring the bug is accurately understood and fixed. At the conclusion of the project, partners will have to handle accessing this support themselves.

People and organization change management and capacity development

By far the largest challenge was to develop a recipe for transitioning different types of partners from cash to mobile payments. This required us to understand an organization’s operational and programmatic processes, and how existing processes could be adapted to encourage beneficiaries and clients to transition to using mobile payments.

Trainings with partner organizations initially consisted of one- to two-day on-site sessions with critical members of staff usually including finance staff, project staff and a member of senior management. Trainings aimed to dive deeply into the organization’s programs and operations, come to a consensus about where mobile money should be piloted, set out roles and responsibilities in the roll out of mobile money and provide an orientation to the Payments or PaymentView software.

Shifting to a change management approach

However, follow-up calls and emails after the first few trainings indicated that organizations were struggling with the change management and client education that shifting from analogue to digital required. This was especially evident in organizations that received incoming payments from clients, as opposed to simply sending out payments. Organizations were being asked to answer questions about how their clients would benefit from using M-PESA instead of cash, how clients would know that their payments were successfully received, and what happened if they were to accidentally send a payment to the wrong number.

SIMLab began working with partners to develop incentives for their clients to shift to mobile money and strategies for how to explain the change to their clients. We increased the frequency of contact with partners, focusing heavily on effectively communicating value propositions to all beneficiaries and stakeholders. To ensure that implementing mobile money is not held up by staff turnover or underperformance of one employee, numerous individuals from each organization were involved.

Focus on the end-user

SIMLab’s new training methodology integrates approaches to client communication and sensitization, tailored to NGOs and SACCOs based on their differing needs and effectively communicating the different value propositions. These strategies help partner organizations explain the benefits of mobile money to their clients and members, as well as to their internal staff. For example, we would stress to SACCO staff that their members would see lower levels of fraud, more secure transactions, a reduction in travel costs and time, improved access to information on loan and savings status, improved communication with SACCO administrators, and could send out quick and easy reminders for meetings and loan repayments. Likewise, with NGOs, we would predict a decrease in time and costs spent documenting and delivering payments, a simplification of payroll and other recurring payments, improved financial management and cash flow visibility, the ability to visualize and easily send financial reports to external stakeholders or board members, and improved contact management (clients/service providers and staff). SIMLab also offered partner organizations a number of client awareness-raising resources they can adjust for their own organization, including draft SMS, flyers, and announcements to be read at meetings.

Key Takeaway

- Partners themselves need to be reminded that change requires time and effort. Initial expectations on the part of the partner organizations were too high in terms of their own capacity to make drastic change. With any innovation, an organization needs to take time to experiment and understand the implications of the innovation on all stakeholders, including executives and management, administrators, program staff, beneficiaries and end users.

Building networks for peer support and learning

Initially, SIMLab trained organizations one by one, but ultimately began running trainings for multiple organizations at a time. This allowed us more time overall with key staff members, and created peer support networks that would provide support once we had left the area, and after the project closes. When two or more similar organizations attend the same training, they are able to learn from each other and quickly build up best practices, as well as have a local partner to discuss issues with such as tracking transaction costs. Additionally, finding and identifying individual ‘champions’ has proven invaluable to keep up momentum on the ground, which also helps to take some of the support burden from the SIMLab team.

Mobile money may not be appropriate for all payments

Some of our pilot partners experienced challenges in attempting to implement digital payments where the human element of the transaction is critical given cultural values, habits and the nature of the transaction taking place.

One SACCO we worked with tried to transition all loan disbursements and repayments. But loans are sensitive: they are not normal transactions. They can result from death, the loss of a home or of livestock, or illness; or they can reflect positive life events, such as a school loan to advance one’s opportunities, a marriage loan or starting a business. A person taking out a loan has likely come to the decision very carefully, and are willing to spend a bit of time and money to acquire. Except in extreme situations, we’ve found that people would much prefer to visit the office of a trusted financial institution to discuss taking out their loan, and decide together with the administrator a feasible loan repayment schedule. The paper loan agreement is significant, and often copied and taped to the wall of their home to remind themselves of the financial commitment they have made. People want to be physically handed at least part of the loan in cash or check, while sitting next to a person who’s job it is to ensure the total loan amount is received. This is about more than receiving a correct loan amount—it’s about seeking guidance, sympathy and shared excitement about the loan and the event it is tied to, with the staff member of their financial institution. Our partner ultimately reinstated loan disbursements in cash or check, and accepted repayments using mobile money.

Key Takeaways

- A huge part of the challenge in transitioning to mobile payments is understanding where mobile payments are beneficial in terms of time and cost savings, and where cash or other forms of value transfer are more economical and culturally appropriate. Without knowing how to implement mobile money, organizations aiming to make the shift to digital payments can easily become dissuaded from using mobile money by attempting to transition all payments in the form of mobile money, or by applying it only to a limited part of programs, creating more work to implement than the benefit derived. Technology has its limits—even if the tool is available it doesn’t mean it should be used in all circumstances. Mobile money should not eliminate human interaction; but rather facilitate payments when human interaction is not possible, too expensive and inundating.

For some of our partners, simply the move from less formal handwritten processes to more formal digitized databases had a huge impact. In moving from analogue to digital records, partner organization Sadili formalized their record-keeping process. When they looked at their digitized records, they realized that only 23 of their 127 members had been paying their dues on a monthly basis. Formalizing their processes increased their income, by shielding their staff—all hired from the local area—from pressure from customers to cut them a deal. Mobile payments can help to reduce fraud and improve accountability, just by removing human susceptibility from the equation.

Once we understood how many variables mattered in assessing probable success and the ability of a partner to make change, we expanded our assessment benchmarks to include users’ computer literacy levels, total staff size, beneficiary type and degree of centralization of financial processes. Nonetheless, some of the organizations we trained did ultimately fail to implement Payments, and are classed as ‘inactive’, specifically because of the barriers to the transition to mobile money: infrastructure constraints, HR capacity, or from fatigue with the process.

Sadili Staff Felix Rullo, Josephine Andeso (standing) and Evelyn Ngoli (seated) test out Payments by sending M-PESA payments during a training. Photo Credit: Dani Dye

Schools just don’t fit the bill

Past success in working with schools meant that schools were included as a target user in the project proposal. However, it appears that schools, being part of a government-run bureaucracy and working on a specific annual cycle, need carefully-timed support and pre-existing internal buy-in that was not possible to achieve on our project timeline. While school is on a break, teachers are also not in school—but pupil payments for tuition (the target of our potential intervention) are made at the very beginning of the term, meaning there is only a very short window of opportunity to introduce the software prior to the day parents would need to begin making mobile payments. Even had they wanted to, school staff required ministry sign-off to make changes to their systems and payment plans.

Successful implementation in schools would require government intervention and funding to overcome their barriers to implementation: resistance from staff and parents, bureaucracy, and scheduling and budget challenges. The learning that has come out of this project could, however, lay the groundwork for government-supported transition from cash to mobile, and SIMLab has already proven in the past that a software such as FrontlineSMS with Payments has the requisite functions to effectively manage such an operation in schools.

Supporting our partners to work with M-PESA

As M-PESA’s project offerings have broadened, the project has required SIMLab to support partners to determine which product is best fit, registered an account, and get up and running. Ultimately, SIMLab worked directly with M-PESA to facilitate access and acquisition of customer to business (C2B) solutions. M-PESA launched their Paybill service in April of 2009, allowing Kenyans to pay their electricity bills straight from their phone. Its aim is to simplify customer to business payments over the phone, without the need for other direct interaction. Many of SIMLab’s partner organizations fit the profile, but we found that, for multiple reasons, small organizations were not taking advantage of the service. Partners consistently reported difficulties procuring the necessary M-PESA business accounts, including opaque processes, lack of feedback, and no training centers in rural areas. After informal consultations with M-PESA staff members, SIMLab worked with Safaricom M-PESA local offices to support partners, reducing the processing time with Safaricom from over three months to just two weeks.

We see the newer Lipa Na M-PESA product, intended to facilitate over the counter mobile transactions, as a response to these difficulties, which must have been reported by small organizations all over Kenya—the product offers some of the essential features of the Paybill service, such as direct integration with bank accounts, but available with much less time and pain. This developing trend and other successes in the mobile money ecosystem may represent the slow maturation of the mobile money market, as it begins to put greater emphasis on users’ needs.

Impact

21 months in, and 6 months after launching Payments, the project has seen large changes in both mobile money and SMS use among participating organizations—but not necessarily tied to the Payments or PaymentView platforms.

SIMLab staff have recruited and trained 44 organizations: 32 NGOs, 11 SACCOs and 1 school. Out of the 44 organizations with which SIMLab has worked, 37 of them had never used mobile money within their organizations and to date 31 of the 37 are at minimum using a Safaricom mobile money business product. 100% of the active partners have experimented with SMS communications to and from their clients and beneficiaries and the majority now list SMS as one of the main communication tools used within the organization.

Out of the 37 partners who remain a part of the project, 14 are using Payments exclusively; 15 are using Paybill with use of FrontlineSMS for sending SMS; 1 is using PaymentView; 1 is using cash; 3 are using M-PESA on a phone; and 2 are not operational for the time being. Those using Paybill were encouraged by SIMLab to do so before Payments was released, as it offered the best value to the organization and their clients. Some partners would prefer to switch to Payments from Paybill, but have been prevented from doing so by the lengthy process required to transition away from Paybill’s online service to a regular M-PESA account.

In most cases partner organizations can point to improved efficiency and cost savings. Prior to using PaymentView, international NGO HealthRight staff physically delivered money to the field, a process that took six hours and placed staff members at risk. Similarly, Mombasa Bunge, Kwale Bunge and Nyamira SACCOs have reduced costs for their members, who no longer need to travel from their homes to the SACCO office to deposit cash for their savings. Nyamira SACCO members reported spending as much as 2,000 Kenyan Shillings for a round-trip from their homes to the bank branch to make loan repayments, reduced now to the 100 shilling transaction costs and transport to an M-PESA agent to load cash onto their mobile wallets. Mombasa SACCO has seen membership numbers increase by 30% since implementing Payments, more members saving and taking loans, and slightly higher repayment rates. The combination of these three improvements have made the Mombasa SACCO more profitable and they are excited to continue using mobile payments and SMS. SIMLab hopes to see more organizations experience significant changes similar to the Mombasa and Nyamira SACCOs in the upcoming months.

Nyamira, Kisumu and Kisii Bunge SACCOs report increased efficiencies in communicating with their members—sending reminders to save extra money, notifications of financial obligations, and meeting announcements—all of which previously took them a few hours to coordinate over voice calls or SMS using their personal handsets. SACCOs are beginning to see greater monthly saving and meeting participation due to an increase in knowledge of the meetings, associated with SMS.

Plans for the future

SIMLab will continue to work throughout 2015 to document the successes of the project, learn from the failures, and motivate organizations to continue engaging with their beneficiaries and clients to explore ways that SMS and mobile payments can increase their opportunities. Project staff will revisit organizations who are not yet fully using Payments and try to migrate them by understanding the barriers holding them back. By the end of the project in December 2015, SIMLab hopes to have resolved any remaining issues partners may have to ensure they’ll be able to continue using Payments and have reliable support on the platform for the foreseeable future. Part of the success of this will depend on ensuring the Payments documentation and user guides are maintained and as detailed and helpful as possible. Another key factor will be to ensure partners are prepared to adapt their operational processes to anticipate change in membership/beneficiaries, group structures and increasing decentralization.

FrontlineSMS, the developers and owners of Payments, are currently exploring a potential business model for the software that will make it a viable product after the end of the current project. They are looking into hardware solutions, such as procuring wholesale smartphones direct from the manufacturer, that would be more feasible in Kenya and allow the software to better transfer to other countries with vibrant mobile money markets.

Conclusion

Through the last 20 months, this project has had plenty of challenges but found success, in sometimes unexpected ways, and in unlikely places. SIMLab set out to assess whether, by supporting SMEs and service providers to implement mobile money, they could address the dearth of businesses offering M-PESA payments and increase the utility of mobile money for people in rural, low-infrastructure communities.

The project has been able to put the highly lauded M-PESA mobile money platform to the test in some of the most difficult and variable contexts in Kenya, engaging with organizations who haven’t yet adopted mobile money despite the existence of business solutions and the strength of the market across the country. SIMLab has created tailored training and engagement approaches to fit varying levels of infrastructure and operational constraints. The project is a strong example of a human-centered approach to mobile money adoption, using agile project management with last-mile organizations.

However, the high-touch approach that was required calls into doubt both the potential of mobile money to scale organically in these communities, and the emphasis we often see on ‘exponentially’ scalable, technology-first approaches within the mobile money space. It may be that the transition from informal to formal, and from analogue to digital business processes, simply requires more support, more time, or both, than many recognize.

Implementers and donors must acknowledge the need for flexible, human-centred project implementation methods which respect local contexts and individual organizations and their business models.

As technology advances, and more tailored technology solutions are developed, technologists need to keep in mind the users they’re building for, and who they may be inadvertently excluding. When it comes to including the most vulnerable, hard to reach organizations and beneficiaries, how can we as technologists ensure users understand the tools available to them? Mobile money, even in arguably the world’s most developed mobile money market, is still a huge challenge for organizations to adopt and one which will require collaboration with governments, MNOs, civil society organizations and technology providers.

Ultimately, although stimulating businesses and improving service delivery is an important outcome of this project, it remains to be seen whether the ultimate aim has been achieved: whether an increase in the number of businesses offering mobile money in the communities in which SIMLab worked will lead to an attributable improvement in mobile money liquidity and an increase in individuals in these communities able to access the benefits of mobile money.

Annex: Partner Profiles

SIMLab is working with 33 NGOs, 11 SACCOs and 1 school across Kenya. Below, a few of the partner organizations experiences with Payments are highlighted:

HealthRight

Size: 1000 volunteers, 16 full-time staff

Area of work: Health and capacity building

Payments Profile: In Elgeyo Marakwet, in the North Rift Valley of Kenya, HealthRight runs projects that rely on a dedicated network of 150 volunteers. All administration is conducted from their head office in Kitale, approximately 100 kilometers away from project volunteers. The administrator at HealthRight uses Payments to pay out stipend allowances to their volunteers on the ground. Now that they’re able to send stipends using mobile money instead of physically handing out cash, they have reduced logistical costs and inconveniences, including eliminating a weekly six-hour drive and security threats.

Mombasa Youth Bunge SACCO

Size: 440 monthly members, 1 full-time staff

Area of work: microfinance and youth

Payments Profile: Mobile money users in the Mombasa Youth Bunge SACCO have increased by almost 100%, saving members time and expenses incurred while making deposits. The SACCO’s membership numbers have increased from 370 to 440 active monthly members, a substantial increase for a small microfinance organization, attributed to member referrals due to satisfaction with an ease of payments and SMS notifications.

Mobile payment tracking has become a quick and automated, process, improving SACCO management accountability. As part of the training, SIMLab has also helped the Mombasa Youth Bunge SACCO to acquire a Paybill account, where M-PESA deposits go directly to the SACCO’s bank account, increasing interest rates. This also removes the need for intermediary cash handling, which is prone to fraud and loss, and carries additional expenses incurred from travel to the bank by the SACCO administration staff.

SCOPE (Strengthening Community Partnership and Empowerment)

Size: 1200 beneficiaries, 10 staff members

Area of work: Poverty reduction, education, and health

Payments Profile: SIMLab’s initial training with SCOPE revealed that their biggest operational challenge was sending and verifying payments. In the past they’ve encountered problems with beneficiaries denying having received payment, staff sending payments to the wrong person, and security. They were initially using Safaricom’s bulk payment system to send monthly payments to approximately 1,200 volunteers, with amounts ranging from 500-1000KSH ($5.46-10.93 USD). However, this system did not offer them the necessary visibility and reliability, primarily because Safaricom’s system requires the internet. SCOPE is now using Payments to send and track all payments. Payments allows them to see all payment details, and include additional notes about the payments, features which are not available through Safaricom. SCOPE is also using the SMS feature of Payments to send health content via SMS to beneficiaries, increasing the effectiveness of health interventions. While Payments is intended to be a mobile money tool, SCOPE has used it to additionally meet their organizational goals by starting a SMS health messaging campaign.

Indicose SACCO

Size: 47 monthly active members, 1 full-time staff

Area of work: microfinance

Payments Profile: SIMLab was referred to Indicose SACCO by an organization in Kisumu who had recently learned that the SACCO was seeking a solution to better manage their payments. The SACCO had recently lost a number of members, greatly impacting their profitability and ability to disperse loans. Prior to using Payments, Indicose operated almost entirely using analogue and cash payments. The SACCO administrator was eager to revitalize the organization with a new tool and believes making the transition from cash to mobile money, plus the added value of sending SMS, will be just what the organization needs to increase membership and profitability.

Indicose plans to send SMS notifications about upcoming meetings, automatically notify people if they’ve missed a payment, and even offer automatic SMS balance inquiries. The SACCO has acquired a Paybill account and anticipates members to begin making Paybill payments. Indicose hopes the ease and efficiency of the process will lead to member retention and expansion.

One of Indicose’s main challenges is that as a community-based organization seeking to reduce poverty, and they have had a hard time sanctioning nonpayers, which has negatively affected the organization as a whole. The SACCO hopes that SMS automation and cleaner financial transactions will help members to better maintain their loans and uplift not only the SACCO, but the community as a whole.

This project was made possible thanks to:

-

2014 State of the Industry Mobile Financial Services for the Unbanked. (2014). Retrieved July 8, 2015. Link (PDF) ↩

-

Mobile money in developing countries. (2014, September 20). Retrieved August 12, 2015. Link (HTML) ↩

-

Kenyans move $12.7 billion on mobile phones in 6 months—Asoko Insight. (2014, August 11). Retrieved September 3, 2015. Link (HTML) ↩

-

Isabirye, N., Floweday, S., Nanavati, A., & Von Solms, R. (2015). Building Technology Trust in a Rural Agricultural e-Marketplace: A user-requirements perspective. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 70, 1-20. Retrieved August 21, 2015. Link (HTML) ↩