Defining Culture Change: Reflections from Code for America's Digital Front Door project commissioned by the City of Oakland, California

36

minute read

Introduction

“This is really about reflecting upon how we have been doing things, and then, changing our culture.”

-Karen Boyd, Assistant to the City Administrator / Director of Communications, City of Oakland

In 2014, leadership within the City of Oakland asked Code for America, a nonprofit organization that builds open source digital civic engagement tools for municipalities, to help them redesign its website.1 At the time, Oakland was seeking an opportunity to reinvent itself: amidst budget cuts that reduced services for Oakland and Occupy protests that highlighted discontent with government generally, the City expressed that it wanted to rebuild trust with its residents. One way that it sought to do this was by increasing accessibility to online services for residents who primarily access the internet via mobile devices. Put simply, Oakland wanted to make its website responsive and user-centered. They named this project Digital Front Door to illustrate the way in which the City’s website has the potential to become the primary entry point for communicating with the City.

In designing user-centered digital products, teams typically begin their work by seeking to understand the individuals who will be using the product that they plan to make. To this end, Code for America’s product team began working with Oakland by engaging in a three month user research phase, hoping to help the City understand how they could redesign their website to best serve its community’s needs. The team produced a thorough report documenting their work during this initial phase of the project. Their report provides an overview of their research methodology, their results, and their next steps planned for the future of the project. It also discusses shortcomings of the City’s current website, which keeps the City from better connecting with its residents - many of whom primarily access the internet via mobile devices.

Unlike the report written by the Code for America team, this follow up piece explores more personal and opinionated accounts of the insights that surfaced during this period. This article hopes to illustrate how efforts to make digital upgrades in governments are about cultural and management changes, in way more so than isolated technological ones. By presenting the views of tech and government professionals who are in the forefront of digital transformation in government, this article intends to provide useful insights for other city decision makers embarking on similar journeys.2 To produce this case study, key members from Code for America and the City of Oakland were interviewed for their reflections.

Individuals interviewed

- Nicole Neditch, Senior Director of Community Engagement, Code for America

- Mai-Ling Garcia, Online Engagement Manager, the City of Oakland

- Karen Boyd, Assistant to the City Administrator / Director of Communications, the City of Oakland

- Michal Migurski, Former Chief Technical Director, Code for America

- Cyd Harrell, Former Product Director and Head of User Experience, Code for America

- Frances Berryman, Former Designer, Code for America

- William Pietri, Former Director of Engineering, Code for America

- Aaron Ogle, Director of Civic Innovation, City of Philadelphia 3

Overview of Digital Front Door, Phase 14

During this initial discovery period, the Digital Front Door team (with members from both CfA and the City) distributed surveys, conducted interviews, and created opportunities for all members of city staff to become involved in this project. Below are brief introductions of these activities.

Surveys

The Code for America team distributed online surveys to learn about who was using the City’s official site, how it was being accessed, and what pages received the most traffic.5 They developed online surveys available on desktop, tablets, and mobile devices and in English, Spanish, Chinese, and Vietnamese. To find participants, the team solicited through the City’s official website, through social media, as well as partnering with local nonprofits who distributed flyers throughout the City. City Council members also helped the team with survey distribution by reaching out to their constituents.

After receiving 1000 responses to their survey (more than twice than they had anticipated) those from Code for America and the City sought to understand whether these responses reflected a cross-section of residents at large. To do so, they mapped out their responses by neighborhood (their surveys asked participants what neighborhood they lived in). In so doing, they found that there was a hole in the middle of the map in which they received virtually no survey participation (they referred to this area as the “donut hole” since it was located in the center of the City). By comparing their survey participation map with a census map, they learned about who lived in the areas that they reached as well as the areas that they did not. From there, they hoped to position the City with clearer understanding of how to focus their outreach efforts in the future so that they could target the communities that were not yet part of the conversation.

Learning from City Staff

From interviews with City staff, the DFD team learned that most staff had high levels of tech competency, including examples of even altering raw code to work around difficult to use software. Many times, people who stated that they were not tech savvy were, in fact, in ways that they did not realize about themselves. Many staffers used the City website to find information owned by other departments or to assist requests from the public (they found that 18% of visits to the site in one month came from city staff). They also learned that the Oracle content management system that the City used at the time imposed processes that hindered quick content updates, even for seasoned users.

Activities with City Staff

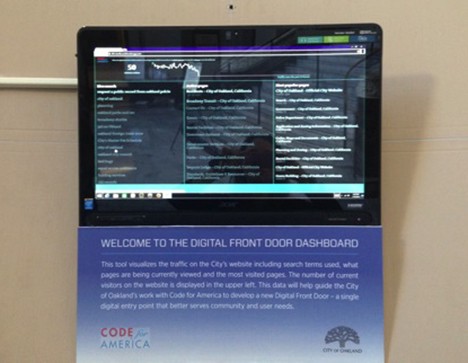

The team wanted City Staff to part of this website redesign process. They installed a dashboard in City Hall so that staffers would be able to understand how the public used the site, and so they could start to feel more invested in the site’s redesign. In this vein, Mai-Ling Garcia, Oakland’s Online Engagement Manager, created several working groups around digital projects, fostering a community of practice among city staff in the website redesign and eventual content production.

Interviews

Nicole Neditch, Senior Director of Community Engagement, Code for America

“…the idea is to shift [city staffers] toward doing ‘what matters most.’”

Nicole has a long history in Oakland: first as an entrepreneur, later, as a member of City staff, and finally, as a member of Code for America, stewarding projects in partnership with the City. Nicole oversaw the Code for America fellowship with the City of Oakland in 2013,6 which led to their engagement in the Digital Front Door project. She currently leads the Digital Front Door team and is responsible for Code for America’s community engagement standards.

Community Outreach

I asked Nicole about the cost and labor involved in reaching communities that are harder to reach. In this case, there were neighborhoods within the center of the city that were not responsive, event after several different outreach efforts. It takes time and resources to keep trying to bring less vocal communities into the fold. On the one hand, the most vulnerable populations might be those who face the greatest obstacles in engaging with the city (there might be technological and language barriers; they may have other reasons for not wanting to interact with the City). How does a city decide how many resources to invest in reaching out? And also, how do cities make sure that they aren’t merely focusing on those who are vocal and participating?

Her response was that it’s a hard problem to solve. She mentioned that when a city is distributing a survey but resources are an issue, one strategy is to limit the sample size so that the overall outreach effort is smaller.

Goals for the Websites

In the DFD Phase One report, the team stated that they ideally hope that 90 percent of people who visit the city website are able to find what they are looking for. In response, Nicole noted that people often visit a City website looking for information about services that fall outside of the City’s responsibility. “Many times there’s an assumption that the site does everything, when that’s not the case. It’s also important for people to know where else to go so that they can’t find the services that they’re seeking – even if they are not services that the City isn’t responsible for. This is why we need to understand what people want – so that we can be able to direct them.”

Finding Champions

While she emphasized the importance of outreach, she also recognized the valuable role of the individuals who are engaged on their own accord. She referred to the Parking Working Group in Oakland, which was a team that had begun working on improving parking-related services within Oakland. The DFD team began piloting their redesign prototypes with this group because it was an existing team of individuals who were committed to bringing about change. When deciding which department to work with for a pilot, she explained that the relevancy of their service is one component but another is the team. “Ask whether they can be champions for the project and whether it will be a priority for them.”

Workflow Changes for City Staff

Nicole noted that adopting a digital first culture within the City of Oakland will enable current staff to focus their energy on substantive tasks rather than on administrative tasks related to website content management. She said that people often express concern that making services more easily accessible online will eliminate jobs of those who process services in person. “It’s important to emphasize that there is still so much for city staffers to do—the idea is to shift them toward doing ‘what matters most’ rather than wasting time dealing with a poorly designed content management system.”

Oakland’s Civic Design Lab

Nicole emphasized the importance of bringing different stakeholders together, which hasn’t been a common practice in Oakland. To help with this, the City is building a Civic Design Lab within City Hall. The Lab will be a space to house interdepartmental collaboration. “When everyone is focused on their own work, they can have many different perspectives,” Nicole explained. She mentioned that if two departments don’t get together, they might generate duplicate pages on resources that have overlap between departments. “It’s helpful for there to be cross-departmental conversation,” she said.

Mai-Ling Garcia, Online Engagement Manager, City of Oakland

“Government isn’t a business, it can’t and shouldn’t be able to choose its customers. Government needs to serve the best interests of the public—its users.”

Mai-Ling is the Online Engagement Manager for the City of Oakland. She develops better digital communications & engagement practices that better serve public needs. She serves as Code for America team’s first point of contact as the City’s project manager/lead and oversees the development of the City’s Civic Design Lab. She created multiple working groups among City staff, fostering broader engagement in a “user first” culture change. She is shaping new web standards and governance for those contributing to the City of Oakland’s website. Additionally, she facilitated the survey distribution and outreach performed by the team.

Community Outreach & Engagement

When I asked Mai-Ling about the labor involved in community outreach and the City’s view on this, her response was that the City has an obligation to serve its residents. “People often say that government should operate exactly like the private sector. I disagree – government can’t target customers – it needs to serve the best interests of the community.” Thus, the City has a need to do tremendous outreach with few resources. There is no ‘one-size fits all’ approach to effective outreach.

A great way to accomplish better outreach is through the selection of several communications tools that can reach the breadth of the Oakland community. These online communications tools can inform better outreach tactics on and offline. Cities, especially Oakland, need to engage and reach a more diverse audience than your average tech company. This means that user research, data and analytics need to be reflective of the Oakland population.

Creating Standards

Mai-Ling stated that if her role was about any one thing, it was about “overseeing and creating a standard process.” She said that the digital practices within the City remained undefined. “At the director level, there are lots of policies in place about how we do things. But they haven’t been written for digital. For example, there’s no social media policy for the City of Oakland. This is great because those who are enthusiastic have freedom. But there are no standards across departments .” Standards enable the City to equalize the services that it provides.

To illustrate the importance of creating standards for content development, Mai-Ling used social media for parks as an example. She explained that if half of the parks and recreation centers in Oakland used social media and the other half did not, those using social media would enjoy benefits that the others would not.

Her example helped to illustrate the power that a city’s use of social media might have in equitable distribution of resources. Because a park that is more visible in social media is more likely to receive attention from the

Web Analytics Club

By showing staffers a web analytics dashboard in City Hall, the DFD team wanted to show them that more people interact with their City government online than in person. If staffers understood this, perhaps they would feel invested in the site and invested in its users. Mai-Ling wanted to take this further by fostering deeper conversations and investigations into the data presented by the dashboard. To this end, she created a Web Analytics Club in order to facilitate a community of practice among city staffers. The club meets on a quarterly basis and generally hosts 6-10 people (around 30 have attended during the past year). Most attendees are content contributors at the mid-level manager level. She states that the meetings are informal, free form, and last an hour and a half.

A photograph taken by Mai-Ling Garcia of the web analytics dashboard on display in Oakland City Hall. Link to source.

Culture Change

Mai-Ling noted that it’s important to foster a culture that celebrates small failures and small, measurable successes. “Failure is a privilege,” she said, in response to a common mantra in tech to fail fast and often. “We’re so resource-strapped. It’s hard when we fail. In government we’re always being told that we’re failing.” Mai-Ling also discussed that defining success might make it easier to get credit for good work. She compared the common government practice of defining success as “adhering to policy,” which isn’t useful to anyone outside of city staff. “If we could define what successful service delivery is, then perhaps we could make the shift to addressing public needs and highlighting our wins.”

A critical component of culture change is creating the physical space to accomplish collaborative work. The Civic Design Lab is being developed as a dedicated space to accomplish interdepartmental work, such as the Digital Front Door Project.

Karen Boyd, Assistant to the City Administrator / Director of Communications, City of Oakland

“Employees are users too. If we make the website better for them, it’s better for the public.”

Karen is the Director of Communications for the City of Oakland. She provided overall project direction for the Code for America fellowship in 2013 and currently guides this Digital Front Door project, playing an integral part in shaping the website as a fundamental communications and service delivery tool.

Community Engagement

When I asked Karen about the team’s low survey response rate from areas in the center of the City, Karen stated that the reasons that some communities remain disconnected from local government are complex. She asked, “what about when people are struggling and don’t have their basic needs met?” Karen pointed to the reality that many people do not have the bandwidth to participate in surveys and for being online, generally. They might be focused on securing food or housing, They might be single mothers overwhelmed with responsibility. They might be ill. And so on. Those who are most vulnerable and likely need city services the most, often face many obstacles in going out and securing them. Regarding the surveys, Karen explained, “the surveys confirmed what we knew already: that it is harder to reach lower income communities with limited English language proficiency that live in densely populated flatland areas.”

Regarding there being a digital divide in Oakland, she agreed but clarified that it’s not merely a result of certain individuals lacking access to computers. She explained, “[there is a] prevailing belief that the digital divide is about some lacking access to technology, but most [low income people] have access to smartphones.” She emphasized the importance of making online services mobile-friendly in order to help bridge this divide. However, she reiterated that the City’s digital divide is about more than just access to technology. She emphasized the value of this research phase in helping the city understand this better.

City Council Members

I asked Karen how the City might become better at connecting with diverse parts of the City. How do you build relationships with those individuals who lead complicated lives and have limited bandwidth? How do you stir their interest and their trust? Karen saw local political representatives as playing a key role. “We found that council members who pushed our survey out got a higher response,” recalls Karen. “Local officials have a deeper connection to the community. They see their constituents every day. They have a level of accountability and they’re tapped into local networks.” Strategically, she noted that, “local officials that used social media have a different reach than those who don’t.”

On Simplifying Bureaucracy

Karen recognized the good intentions behind the slowness within government. “Bureaucracy exists to create checks and balances, to level the playing field for small and large.” But she also recognized that it makes processes more constricted. This harkens back to her talk at the 2015 Code for America Summit in Oakland, during which she asked each member in the audience to imagine that they are about to jump out of an airplane. First, she asked them to imagine that right as they are about to step out of the plane, someone hands them a “962 page government manual with the instructions” on how to activate the parachute. After pause, she asked them to alternatively imagine that instead, just before jumping, someone hands them a little card that says “pull cord to release parachute.”7 She used this example to illustrate the difference between content that adheres to policy and content that provides what the user needs.

Karen was sympathetic toward tendencies within government to be cautious and procedure-oriented. “There is so much mistrust and anger expressed toward government at large so a natural reaction is to want to get something perfect before putting it out in the open.” But she also discussed ways in which shorter, simpler content will enable more people to understand what’s happening in their City government. She showed me legislative documents from City Council meetings and explained that the website currently lists links to these documents for anyone who is interested in learning about them. But reading these documents takes a lot of time. Karen said, “what if we could present short, readable summaries on our website so someone visiting could understand them after doing a quick scan?”

Karen also talked about culture change, in the context of city staff adopting an iterative and collaborative work process through which staff members put work in the public sphere faster and have feedback loops (such as analytics) available to let them know the quality of their work. It is contrary to the usual, risk-averse sensibility of government, but she recognized that working in this way could, after a transition period, lessen the load of city staff, enabling them to work on a more substantive level. Instead of painstakingly working on something until it is perfect, in an iterative environment, staff can push content and receive feedback loops letting them know if the content serves its purpose or if it needs to be changed.

Michal Migurski, Former Chief Technology Officer, Code for America

“You don’t need a team of engineers to build and maintain a city website that effectively delivers services to its users.”

Mike was the Chief Technology Officer at Code for America during this three-month discovery phase.

Simplicity

Mike explained that the simpler the design of a site, the easier it will be to make it responsive and functional for mobile-first users. When cities hire outside firms to develop their websites, Mike encourages them to go with a design team that understands the value of keeping the technology simple. “It’s so easy to get it right,” Mike stated. “You don’t need a team of engineers to build and maintain a city website that effectively delivers services to its users.” Additionally, you don’t need to be a developer to make meaningful contributions. “There is a woman in City Hall who has taken on making the City’s PDFs machine readable,” Mike recalled. “Everyday, she takes a few documents. She’s a hero.”

Additionally, Mike emphasized the value of simple language. He recalled the simplicity of the language and content on translated pages within Oakland’s website. “Non-English pages on Oakland’s website were much simpler and minimal due to the cost and labor associated with translation; they only contain the most essential information. I found that these pages were often better designed than the English pages, which were full of images and unnecessary information.” Mike also underlined the importance of simple language for emergency information because when there is an urgent message, simple language increases chances of reaching broad audiences.

The difference between apps and websites

“Apps don’t appear in Google searches as websites do,” Mike explained. When people seek a service, they commonly perform online searches, and the city’s website will likely appear in the results. Cities that rely on apps to deliver services have to maintain both their website and their apps. It’s better to keep things simple and maintain a website that is responsive, and works on mobile devices.

Community Outreach

Mike and others recall that when they began the project, they had assumed that the city would have connections with a cross section of the whole city population. “We had a naive idea that Mai-Ling and Karen would have a rolodex of community points of contact such as local ‘boxing teachers and preachers.’” When they learned that no such rolodex existed, the DFD team had to develop new strategies for community outreach, which was not something that they had anticipated they would have to do. To connect with people from parts of the City that were historically less involved in the city’s community engagement initiatives, Mike reached out to grassroots figures who were willing to push surveys out to their constituents. Susan Mernit of Oakland Local, a locally produced non-profit news source, was one person that Mike said was particularly helpful with their outreach. Susan had street teams help them distribute thousands of flyers throughout different parts of the City.

“But why even bother reaching out to communities who don’t express an interest in getting involved in the first place?” I asked. In response, he recounted the 2013 launch of Google Fiber in Kansas City. At that time, Google sought to initiate Google Fiber there, which would enable residents to have faster, more reliable internet connections for less cost. To figure out where to begin laying down fiber optic cables, Google ran a campaign during which they offered free installation to neighborhoods with the highest rate of residents who expressed their commitment to purchasing Google Fiber services in the future. However, by soliciting participation from paying customers, Google essentially perpetuated disparate access to resources that were institutionalized during a period of time in which racial segregation and discrimination was culturally acceptable.8 To Google’s credit, and with help from Kansas City community-based organizations concerned with digital inclusion, they changed their outreach strategy so that their reach expanded beyond the communities that initially responded to their offering.9

Mike cited this example to demonstrate how complicated community outreach can be for cities as well as how important it is for cities to be thoughtful about the outcomes of their outreach. I asked how one knows when enough user research has been performed. He acknowledged that that you can never really know everything and ideally would do multiple rounds of surveying. But he also clarified that sometimes time and resource constraints make doing so impossible. Recognizing this, he answered that you have done enough research when you have what you need to move to a next step. He also mentioned the importance of being forthright by documenting the limitations of your research methods. In the DFD team’s case, they stopped when they found that they had developed new insights and had positioned the City well for a next round of surveys.

Cyd Harrell, Former Product Director and Head of User Experience and Frances Berriman, Former Designer, Code for America

“When you remodel your house, even if you don’t know much about construction, you still know what you need. Cities should become responsible for knowing what their residents need.”

Cyd and Frances are designers and our conversation focused on user experience research and design. I interviewed them together.

Regarding the Needs of Users

Cyd and Frances both shared a vision of cities eventually having a more in depth knowledge of the needs of their users, which they could use to inform their websites’ design. “There’s the “’trifecta of doom,’” Frances explained. Residents, businesses, visitors - these are categories that often structure city website navigation due to a common but faulty assumption that they are the primary users of these websites. Frances explained that building web content for assumed users is a bad idea. Cyd chimed in, “the state of municipal websites is awful. There are patterns; [with most of them] it’s clear that no one had researched the needs of users.”

Instead of building for anticipated users, Cyd emphasized the need for cities to make a practice of understanding their real user base. Cyd strongly suggested that cities learn about the diverse needs of their residents, and that they use that information to shape their service delivery. She clarified that this is independent of any technological task involved in website development. Cyd likened cities to a person remodeling her home: “When you remodel your house, even if you hire someone to do the job, and even if you have no knowledge about construction and architecture, you still know what you need.” The question then becomes a strategic one: how a city manages outreach efforts and which departments take on what responsibilities to maintain relationships in the community. Cyd explained, “you need to begin with research so that you can understand the community. This way, when you have data, you are prepared to ask the right questions.”

Frances discussed the importance of understanding user needs due to the opinionated nature of software. She explained that all software inevitably imposes a structure on the people who use it. Take WordPress, for example: it encourages users to write content in a chronological blogging style. If a user wants to do something outside of this model, she’ll have to create solutions to do so, which is far more work that going with the software’s existing templates. Without understanding users, software developers can create products that are uncomfortable for the people who use them, and that push users to work in ways that run contrary to their needs and wants.

City staff as users

Both Cyd and Frances were clear to say that while residents are one user of a city website, city staff who write content for and maintain the city website are another. And regarding city staffers, “[they] are commonly very hands off with their websites,” Cyd explained. “We commonly hear people tell us, ‘I’m not technical.’” Frances explained that one reason might be that the software often used for municipal websites is “abusive” towards the city staff who have to interact with it. She mentioned the many levels of approval that city staff in Oakland had to secure before being able to push new content to the site. “Look at Mai-Ling’s inbox and you’ll see endless emails requiring her attention before the site will accept her content changes,” Frances added. She explained that the current software that Oakland uses inherently doubts the competency of the people who make changes. “The software treats its users as though they are stupid,” she said.

Frances discussed the ways in which she wanted to see software used by cities make their users feel confident and enthusiastic about their abilities. As she and others from the DFD team began prototyping a new CMS, they were very intent on addressing this particular problem - the “abusiveness” of existing city website software. Both Cyd and Frances explained, “what we hope to help city staff to understand is that (1) they are actually much more technically savvy than they realize, and (2) that a well designed content management system is one that is a pleasure for them to use.”

Caveats About Working with Large Companies that Build Municipal Websites:

Cyd warned cities to be careful if any company offers to provide design, content, hosting, migration of old content, insurance, research, and possibly other services. She explained that it’s too much for any one entity to have expertise in all of these areas. In the end, these contracts often result in suboptimal outcomes. “We heard about a contract in which a city paid $100,000 for what was essentially five Photoshop files. And the City didn’t use Photoshop. They had to buy Photoshop just to open them.”

William Pietri, Former Director of Engineering, Code for America

“Rule of thumb: if it looks like an organizational chart, then it is convenient for the writers, not for the users.”

William joined the Digital Front Door team as Director of Engineering, leading the development of a content management system for municipalities. Although he started after this initial research phase had been completed, his work was informed by the research conducted in phase one.

Defining Success and Failure

William recognized that cities are risk-averse, in part because that they have limited resources, and that they provide services to vulnerable populations who rely on them. But he also understands this to be the result of a system that rewards those who maintain the status quo. His response was that Cities should be less afraid of “failing” by trying out something new because they are already failing their constituents every day so long as their websites fail to connect them the services that they seek. He expressed the need for a new measure of success based on the success of the tools rather than compliance with established procedures.

Feedback Loops

William comes from a product development and agile management background and was passionate about moving municipal websites away from looking like organizational charts, and toward serving users. He was particularly interested in the idea of developing editing tools for City staffers and talked a good amount about the value of working on smaller pieces at a time and building in feedback loops so that every time a contributor to the site generates content, he or she can get feedback as to whether or not it serves its purpose. William discussed the potential for making content generation less daunting for City staffers with a tighter system of feedback loops in place. He referenced Hemingway Editor,10 which analyzes text and suggests ways to make it clearer and simpler. William explained that if someone working for the city could write website content and immediately get feedback on the language without waiting for a supervisor’s review, the process would take less time. Also, the experience of writing might be less stressful and staffers might learn faster how to write clearly and simple for the web.

Aaron Ogle, Director of Civic Technology, City of Philadelphia

“Having a content designer is completely necessary. I don’t know how you can do municipal website redesigns with any significant degree of quality without someone thinking about these things.”

When Aaron Ogle began redesigning the City of Philadelphia’s website, he used the DFD survey for his initial outreach efforts. Both Cyd and Mike suggested that he be interviewed for this case study.

User Research and Community Outreach

In Philadelphia, Aaron’s team began redesigning the City’s website by focusing on building a prototype and putting it out in the public sphere for feedback. Afterward, he hired Erin Abler, a content designer, to join the team. Aaron explained that bringing Erin on his team helped him realize how much more focused his build could have been had he dedicated more time to research in the very beginning. “It’s a different mentality than the one that I come from being from software, which is about building and iterating,” Aaron explained. “By not doing the research at a city-wide level, we missed out on that 10,000 feet view from which you can look at the city as a whole rather than department by department.”

Aaron continually emphasized the value that having a content strategist in his department. When I asked what made Erin so good at her work, Aaron explained that she has a combination of strong communication skills as well as a good sense of how to develop a navigation structure based on user needs. He stated that Erin can articulate her ideas well in writing as well as verbally, and she is an information architecture “whiz.” “Having a content strategist is completely necessary. I don’t know how you can do municipal website redesigns without any significant degree of quality without someone thinking about these things.”

I asked him how to know when you’ve done enough outreach, he answered, “I don’t know if that’s a question that we should answer. Maybe it’s something that we need to keep working on. There is a layer of improvement that you can do. Just because there’s a deeper place to go, doesn’t mean that the one layer of improvement isn’t valuable. We’ve kept going. Now we have a user experience strategist and we’re combining her research expertise with web analytics and 311 data to paint a broader picture of the city.” He explained that his hope for the site is that “people will be able to find what they are looking for where they expect it, then they will be able to understand it and act on it.”

Limits of Analytics

Aaron explained that “analytics offer a particular perspective: they can tell you where people are going [on the website], but they won’t tell you their experience: how frustrated the visitors are, whether they found what they were looking for, things along those lines. Analytics can’t tell you about the gaps, can only measure what’s there.”

Federal Front Door

Coincidentally, 18F, an in-house consultancy dedicated to improving digital services for federal agencies, recently published writings about their project, *Federal Front Door, *a content management system intended to help federal government entities maintain websites that focus on serving the needs of individuals who visit the site and rely on agencies for services. The title is similar as teams at both 18F and Code for America imagined the web as the point of entry for individuals seeking government services. They have released an introduction to the series on their website, a complete pdf of the research findings, and a new microsite that details the themes the research team is investigating.

Conclusion

The City of Oakland is in its final stages of working with Code for America by redesigning several select pages on the site together. In several months, Code for America will hand off this project, leaving the City in charge of the rest.

If there is any simple takeaway, it is that all of these interviews emphasize the community effort that is required to make a responsive and user-centric municipal website, and the ongoing human relationships that form the foundation of good civic technology efforts. These ongoing relationships and processes don’t merely start and stop within the timeframe of a contract with a technology vendor; they require ongoing effort to keep up. User-centered design requires continually updating one’s knowledge about users, and an agility to quickly change and respond to what users want and need.

In a recent blogpost about Australia’s site, gov.au, by Leisa Reichelt, the Director of Australia’s Digital Transformation Office (DTO), she wrote,

“We need to come together to write content that meets user needs, not content that is convenient to our organisation’s [sic] structure. Then we need to do user research to make sure that people can find and understand the content, and then use the research findings to continually improve the content until it works for everyone who needs it.”11

Reichelt’s sentiments echo those expressed in the interviews presented here. I list her voice at this late stage in this article only to communicate that many people in governments all over the world are going through a similar transformational process at this moment. Different administrations are figuring out how to set infrastructure in place to support the production of simple content that users want and need is a great goal for governments to have. But all continually explain that to do so requires a new way of working. It’s not enough to hire a large company to steward a technological upgrade. Instead, all of city staff need to learn new ways of working collaboratively and writing in ways that help the public interact with their cities. And to do this, cities need to understand the needs of their constituents. It’s a shift, but it seems to be doable, and perhaps one that makes working for a city more exciting, more engaging.

Footnotes

-

The current City of Oakland website is http://www2.oaklandnet.com/. Accessed on March 21, 2016 ↩

-

I’ve given the organization of this case study a lot of consideration. On the one hand, I thought about structuring this writing around recurring themes, namely, the necessity for performing qualitative research, addressing bias, and changing content production methods across city departments. But then, I also liked the idea of organizing this piece by the different individuals who generously shared their thoughts with me. In the end, I felt that fitting personal voices into themes editorialized more than I wanted. So I left the sections structured around the speakers. ↩

-

As Director of Civic Technology for the City of Philadelphia, Aaron appropriated the DFD surveys for user research that he performed in Philadelphia in furtherance of the redesign of their city website. ↩

-

This is a quick overview. For a more thorough account, see http://www.codeforamerica.org/our-work/initiatives/digitalfrontdoor/oakland-phase1-report/ ↩

-

The team only used online surveys due to the short term of the project, which would not accommodate their small team to additionally distribute and process paper surveys. This limited the potential participant pool to computer users rather than representing the entire resident demographic as is. The high level of reported internet access reported in the survey was likely influenced by this. ↩

-

During the preceding year, fellows from Code for America who were assigned to partner with the City of Oakland, built RecordTrac, a online application intended to help the City manage incoming public record requests (see http://records.oaklandnet.com/). ↩

-

Boyd, Karen. 2015 Code for America Summit. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Eph5S1d35eg. Accessed March 21, 2016. ↩

-

See Wohlsen, Marcus. “Google Fiber Split Across Kansas City’s Digital Divide.” Wired. September 7, 2012. http://www.wired.com/2012/09/google-fiber-digital-divide/. Accessed on March 21, 2016) ↩

-

See Wohlsen, Marcus. “Most of Kansas City Set to Get Wired With Google Fiber.” Wired. September 10, 2012. http://www.wired.com/2012/09/most-of-kansas-city-set-to-get-wired-with-google-fiber/ Accessed on March 21, 2016) ↩

-

This online editing tool, hemingwayapp.com, was introduced to the engineering team by Norris Hung, a front end developer at Code for America. ↩

-

https://www.dto.gov.au/blog/gov-au-is-not-a-technology-project/) ↩